|

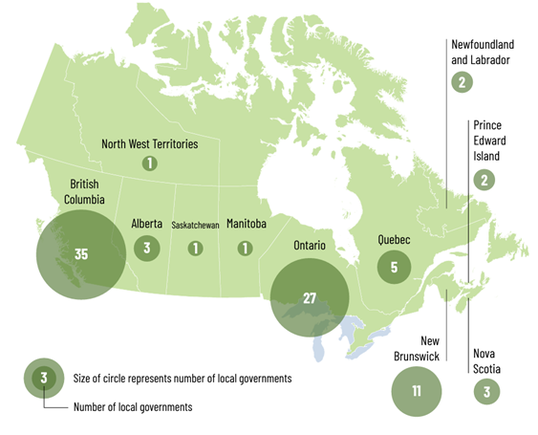

11/17/2022 Wetlands for well-beingAuthored by Rachel Buxton on November 16th, 2022  Photo by Danny McIsaac Photo by Danny McIsaac The chorus of frogs croaking, the slow ambling of a turtle, these sounds and sites of wetlands delight Ontarians. It turns out, experiences in wetlands are more than delightful – they’re good for our health. Experiencing nature has a range of health benefits, from boosting memory retention to increasing life span. Nature does not require our direct attention, like the constant stimulation of being in a city, allowing recovery from stress. Connecting with nature makes us happy. Also, nature was central to getting many people through the COVID-19 pandemic, buffering mental health during stressful experiences. Wetlands have unique features that make experiences in them particularly good for our well-being. They house high numbers of species, particularly those that sing (birds) and croak (frogs). This results in an environment rich in natural sounds, which are known to be a big contributor to nature’s health benefits. A recent study that spanned 18 countries showed that visiting natural spaces like wetlands decreased mental distress and increased feelings of positive well-being. Some health care professionals have even started prescribing their patients time in wetlands to treat anxiety and depression. Importantly, wetlands save us health care costs. For example, in the UK, London’s natural spaces alone are estimated to save £950 million a year in physical and mental health costs. As the global prevalence of mental health continues to increase, we won’t have enough primary care to meet growing demand. Why not let nature, the ultimate healer, do its job! Wetlands protect our health – it’s our responsibility to protect their health and #saveOntariowetlands. Authored by Emily Ury and Nandita Basu on November 11, 2022  Wetlands are often referred to as the earth’s liver, because much like the liver does in the body, wetlands remove toxic substances and pollutants from the environment. But how do wetlands improve water quality? Wetlands are like sponges. They soak up flood waters, holding onto them in their soils just long enough for plants, insects, and the microorganisms that live in wetlands to get to work. All of these living organisms act as the first line of defense against pollution. Wetland plants take up excess nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorus, from lawn fertilizer and animal waste, preventing it from reaching our streams and lakes where it can lead to harmful algal blooms. Plants can also take up heavy metals, like cadmium and copper, known for their deleterious health effects. Microbes can break down organic pollutants like pesticides, which can be potent neurotoxins. Finally, many of the toxic chemicals that enter wetlands simply get trapped and settle into the soil, where they get buried. This trapping of harmful substances effectively protects plants and animals (including people!) from exposure. When we consider how many different kinds of harmful chemicals and pollutants we emit into the environment, it is no wonder why wetlands are so important. In conventional water treatment plants, each pollutant might require special treatment steps in order to be effectively removed, and ultimately, these costs add up. But, just how much is the cost of conventional water treatment? Are wetlands really that valuable? In a word, YES. The money value of wetlands cannot be understated. The tax burden of maintaining clean water without the help of existing wetlands would be felt by everyone. It is estimated that a small wetland of only one hectare (about the size of a football field), saves about $1,000 in water treatment costs every year, adding up to billions of dollars in Ontario alone. These small wetlands are the most threatened by development and urban sprawl, but it is essential that we maintain a healthy distribution of small wetlands throughout the province to protect us from harmful water contamination. Another way of thinking about the impact of wetland loss, is to consider the downstream effects. When you replace a wetland in an urban or suburban neighborhood, you might not notice the deterioration of your own water quality, but the consequences travel downstream. Think about how often we experience beach closures in our lakes due to harmful algal blooms. The problem of contamination in our lakes will continue to grow, if we lose the purifying power of our urban and agricultural wetlands. Southern Ontario has already lost over 70% of its natural wetlands, losing the rest could have devastating consequences. A study conducted in the Mississippi River Basin in the US showed that the loss of existing wetlands would double the nutrient load to the Gulf of Mexico, thus aggravating the massive hypoxia and algal bloom challenges that currently exists in the region. The cost of reducing the phosphorus pollution that is currently causing the same water quality problems in the Great Lakes is estimated to be $3 billion CAD. This cost, and the cost to our tax payers, will only increase if the destruction of wetlands is allowed to continue in Ontario. Loss of wetlands in Ontario will be felt by everyone, either through our wallets, as taxes are raised to compensate for rising water treatment costs, or through our declining health from exposure to contaminated water. Let’s not let this be our fate. Take action: contact your MPP or submit a comment to the standing committee reviewing Bill 23 by midnight November 17, 2022. Read more about the proposed legislation changes and why you should act! 11/11/2022 The Financial Benefits of WetlandsAuthored by Joanna Eyquem (Managing Director, Climate-Resilient Infrastructure) and Kathryn Bakos (Director, Climate Finance and Science, Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation) on November 11, 2022  Wetlands are not just “nice to have” – they provide services that are of direct financial benefit to our communities. These services include soaking up and storing water to reduce flood risk, helping to keep water flowing during times of drought, filtering our drinking water and reducing extreme heat in urban areas. When we lose wetlands, we also lose all of these services. However, this loss is not transparent since the financial value of wetlands does not routinely figure on our balance sheets. The good news, as outlined in the recent report Getting Nature on the Balance Sheet: Recognizing the Financial Value Provided by Natural Assets in a Changing Climate, is that over 90 local governments across Canada are working to identify and value services provided by natural assets, such as wetlands, including 27 local governments in Ontario. Work within these communities has focused on valuing services that local governments are responsible for, for example provision of clean drinking water and flood protection. So what are wetlands “worth”?

Economic valuation studies outline examples of significant, “hidden” financial benefits of wetlands, focused on specific community services. Water filtration In Southern Ontario, University of Waterloo researchers, Tariq Aziz and Philippe Van Cappellen found that wetlands provide an estimated $4.2 billion worth of water filtration services each year. If these services are lost, communities would need to treat the water by building and maintaining costly grey infrastructure solutions. Flood protection The report Combating Canada’s Rising Flood Costs: Natural infrastructure is an underutilized option demonstrated the significant value of flood protection provided by wetlands drawing on examples from across Canada. For a rural case study in Ontario (in the Credit River watershed), flood damages were 29% ($3.5 million) higher when headwater wetlands were assumed lost to agriculture. In an urban case study (Uptown Waterloo in the Laurel Creek watershed) estimated flood damages were 38% ($51 million) higher without the wetlands. These estimates were also noted as conservative. If wetlands are lost to urban development rather than agriculture, the increased runoff from impervious (waterproof) urban surfaces (such as buildings, roads and parking lots) is likely to further increase flood damages. You can find more details of each case study in the report When the Big Storms Hit. Carbon storage and sequestration As communities implement plans to reduce greenhouse emissions and reach net-zero, wetlands are again on our side. According to the Geological Survey of Canada, Canada’s wetlands hold almost 60 per cent of all the carbon stored in soils across the country. As an example at the local level, wetlands within the National Capital Region are estimated to provide climate regulation services to a value of $ 2.9 million per year. A parting thought Wetlands are essentially our front line allies in tackling climate change and biodiversity loss. Preserving these habitats is a cost-effective way to maintain services of financial value to our communities. It is more complex and costly to restore wetlands once they are lost, or to replace the essential services they provide with grey infrastructure. Authored by Lenore Fahrig, on November 10, 2022  Blanding's Turtle, photo by Jennifer Angoh Blanding's Turtle, photo by Jennifer Angoh Unlike large wetlands, most of Ontario's small wetlands currently have no protection, and Bill 23 would remove what little protection they do have. This is a big problem for Ontario's biodiversity. When a small wetland is drained or filled to build a home, a few plants, turtles, frogs, birds, and other wildlife lose their homes. When another small wetland is drained or filled to build another home, a few more plants, turtles, frogs, birds, and other wildlife lose their homes. While each lost small wetland by itself might not seem like a big deal, altogether the accumulated loss of small wetlands is a huge deal for Ontario's biodiversity. It's like this. Say someone steals $10,000 from you by removing $1,000 from your savings account every day for 10 days. The impact of that theft on your life would be just as big as if they stole the whole $10,000 all at once. It's the same, and worse, for wetland loss. Ten small wetlands together actually hold more biodiversity than a single large wetland that is the same size as the ten small ones put together. This means that the destruction of the ten small wetlands, one at a time, has an even bigger impact on wetland biodiversity than the destruction of the large one. In southern Ontario, we have already lost about three-quarters of the total wetland area that was here before European colonization. So, we have already lost three-quarters of the potential homes for wetland wildlife in southern Ontario. This is why in Ontario we have many threatened and endangered wetland species. And this is also why every remaining bit of wetland in Ontario, whether big or small, is precious to Ontario's wetland biodiversity. We can accommodate our growing human population by increasing housing density within the already-developed areas of towns and cities. However, the same option is not available to wetland species. In southern Ontario, to provide homes for wetland wildlife and prevent their extinction, we need to protect all remaining wetland areas. Despite this, Ontario law allows the destruction of most small wetlands, simply because they are small. The one category of small wetlands that can be protected under Ontario law is the small wetlands that form part of a larger group or "complex" of wetlands. But Bill 23 would remove even this protection for small wetlands in Ontario. This would place at even greater risk the plants, turtles, frogs, birds, and other wildlife who call these wetlands home. Want to know more about changes that would erase small wetlands? Read this blog

11/10/2022 But isn't housing important?Authored by Rebecca Rooney and Courtney Robichaud, November 7 2022 Ontario faces a crisis of housing affordability, but Bill 23 - the More Homes Built Faster Act - will not solve the problem.

Wetlands are our allies in sustainability.

This is why Save Ontario Wetlands is calling on the provincial government to stop Bill 23, drop changes to the Ontario Wetland Evaluation System, and honour their promise to protect the Greenbelt. Authored by Kim Kleinke, Marissa Davies and Maria Strack (Wetland Soils and Greenhouse Gas Exchange Lab) on November 9, 2022  In the face of the climate emergency, you’ve probably heard “save our rainforests” or “plant two billion trees”. We’re producing too much carbon dioxide (CO2) and causing climate change. Trees uptake CO2 and cutting them down releases it back to the atmosphere, so it seems like a no-brainer to protect and plant trees. But what other important ecosystems do we have? Maybe you know that the ocean absorbs a lot of CO2 (about 30% of what we release into the atmosphere). What you may not know about is the importance of wetlands. Like forests storing carbon in trees, wetlands hold carbon underground in soil, and in northern regions, they currently store over 30% of the soil carbon while only covering around 3% of the total land area! Wetlands being wet means that decomposition is slow (think of how well “bog bodies” are preserved). Slowly decomposing plant litter and other organic materials hold onto their carbon and do not release much CO2 into the atmosphere. The CO2 that is slowly released is outbalanced by the living plants, including trees, actively sucking up CO2. With this imbalance, carbon is consistently stored in the decaying organic matter leading to carbon rich soil, often called peat. So, wetlands act like a bank account for carbon that is stored beneath our feet. But, this storage takes time, building up slowly over thousands of years. Canadian wetlands cover about 13% of our land area and account for almost a quarter of global wetlands. Unfortunately, wetlands and their importance often fly under the radar when it comes to land use planning and are not given the protection they deserve. Across Southern Ontario, we have lost about 56% of our wetlands to human development - in some places as much as 90%! Just like cutting down the rainforest, draining or building over wetlands causes us to lose both the active uptake of carbon and a large amount of the stored carbon. Once wetlands are no longer wet, the organic matter in the soil starts to decompose more quickly and carbon is released. Our development in Southern Ontario has released wetland carbon stocks leading to a reduction in the carbon stored of 2 billion tonnes since the 1800s. This loss is equivalent to the average annual greenhouse gas emissions of over a billion gasoline cars! While wetlands can be restored or even constructed, the long-term carbon stocks are not quickly recovered. The process of carbon storage in wetlands is slow and restored wetlands may not recover their natural ability to store carbon for many years or decades. Wetlands are significant carbon stocks and have a high potential to mitigate climate change if properly protected and managed. Avoiding wetland disturbance provides more climate benefit than restoring areas that have been disturbed. With our large wetland area and their importance for climate action, we as Canadians have a responsibility to protect these forgotten ecosystems. Take the time to learn more about wetlands and what you can do to help. Authored by Autumn Watkinson, November 9 2022 Turtles can’t talk, but if they could, they would tell you that their livelihood in southern Ontario is hanging by a thread.

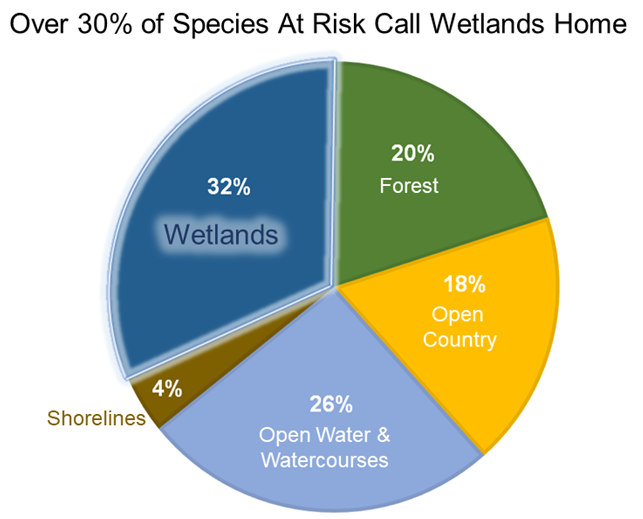

A map turtle A map turtle Under Bill 23, changes to Ontario’s Wetland Evaluation System (OWES) will make it harder for a wetland to be classified as Provincially Significant. Provincially Significant Wetlands are afforded protections to ensure that they are not developed or altered. Currently, the Special Features category under OWES considers a wetland’s value as habitat for threatened or endangered species … but changes to OWES under Bill 23 will remove this consideration, meaning still less protection for the province’s most vulnerable flora and fauna. Even with protections to species at risk habitat afforded under the Endangered Species Act, Ford’s government has granted thousands of permits allowing harm to species at risk and their habitats. Continuing to remove protection for species at risk and their habitats will only make it easier for critical habitat to be destroyed. Bill 23 would also see smaller wetlands that contribute to larger wetland complexes lose protection. Although small patches of habitat may not seem as important as larger areas of unfragmented habitat, recent studies have shown that a group of small habitat patches can host as many or more species than a large patch. As more and more smaller habitat patches are destroyed, the connectivity of larger wetland complexes will also be lost. These smaller patches become islands, isolated from the larger mainland, surrounding by a sea of human activities. For species at risk, this might mean that movement between habitat patches is no longer possible or that they will have to traverse a dangerous, anthropogenic landscape to reach their destination. Without being able to move between wetlands, species are more vulnerable because they cannot escape any adverse changes that may occur in their home wetland. And by traversing longer distances between wetlands, species increasingly encounter roads, which are the leading cause of morality for turtles and other herpetofauna. Both scenarios further increase threats of these already extremely vulnerable species.  A Blanding's turtle A Blanding's turtle Ford’s government has already demonstrated they do not consider the cumulative affects their actions have on species at risk. Since 2007, Blanding’s turtles have been impacted by 1,403 individual approvals for harmful activities, with no regard for the cumulative impact this would have on the species. Under Ford’s government, we’ve already lost habitat protection for many species at risk and there is no long term plan to improve the overall state of species at risk in the province. Further negative changes could be so detrimental that we lose some of these species forever. Turtles can’t talk, but if they could, they would tell you that their livelihood in southern Ontario is hanging by a thread. Please speak up for Ontario’s species at risk and take action to #SaveOntarioWetlands!

Authored by Rebecca Rooney, November 7th 2022 New to The Ontario Wetland Evaluation System? Read this helpful primer first. Changes to OWES related to Bill 23 – the proposed More Homes Built Faster Act – undermine the wetland report card in 3 key ways:

3. The OWES changes introduce “re-evaluations” so that already-evaluated Provincially Significant Wetlands can be re-classified using the new designed-to-fail OWES. OWES files have always been considered “open files” subject to updates, but some conservation authorities worry this change will put nearly all remaining wetlands on the chopping block. Don’t let our valuable wetlands be destroyed to make way for sprawling, unaffordable single-family homes. Take action to #SaveOntarioWetlands!

Learn more about the importance of small wetlands here

Authored by Rebecca Rooney, November 7th 2022 When Ontario introduced the science-based Ontario Wetland Evaluation System in 1984, it was truly pioneering. Called “OWES”, it was one of the first tools to measure the functions and values of wetlands to inform their management in North America. Ontario has remained a leader in wetland evaluations, updating OWES as new science and technologies became available.

OWES is pretty sophisticated, but the concept is simple: it’s a report card that a certified evaluator completes to grade a wetland in four “subjects”: Biological, Social, Hydrological, and Special Features.

The local Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry office reviews the OWES report card.

Provincially Significant Wetlands are supposed to be protected and the benefits they provide to society, the economy and the environment preserved for the long-term benefit of Ontarians. Read how proposed changes to OWES will affect wetlands in Ontario here. |