The financial benefits of wetlands

Authored by Joanna Eyquem (Managing Director, Climate-Resilient Infrastructure) and Kathryn Bakos (Director, Climate Finance and Science, Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation) on November 11, 2022

Wetlands are not just “nice to have” – they provide services that are of direct financial benefit to our communities. These services include soaking up and storing water to reduce flood risk, helping to keep water flowing during times of drought, filtering our drinking water and reducing extreme heat in urban areas. When we lose wetlands, we also lose all of these services. However, this loss is not transparent since the financial value of wetlands does not routinely figure on our balance sheets.

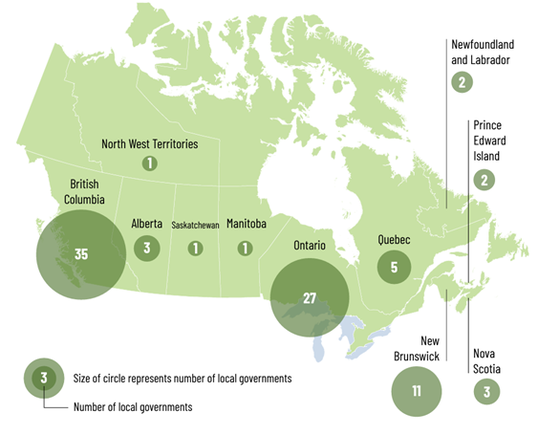

The good news, as outlined in the recent report Getting Nature on the Balance Sheet: Recognizing the Financial Value Provided by Natural Assets in a Changing Climate, is that over 90 local governments across Canada are working to identify and value services provided by natural assets, such as wetlands, including 27 local governments in Ontario. Work within these communities has focused on valuing services that local governments are responsible for, for example provision of clean drinking water and flood protection.

So what are wetlands “worth”?

Economic valuation studies outline examples of significant, “hidden” financial benefits of wetlands, focused on specific community services.

Water filtration

In Southern Ontario, University of Waterloo researchers, Tariq Aziz and Philippe Van Cappellen found that wetlands provide an estimated $4.2 billion worth of water filtration services each year. If these services are lost, communities would need to treat the water by building and maintaining costly grey infrastructure solutions.

Flood protection

The report Combating Canada’s Rising Flood Costs: Natural infrastructure is an underutilized option demonstrated the significant value of flood protection provided by wetlands drawing on examples from across Canada. For a rural case study in Ontario (in the Credit River watershed), flood damages were 29% ($3.5 million) higher when headwater wetlands were assumed lost to agriculture. In an urban case study (Uptown Waterloo in the Laurel Creek watershed) estimated flood damages were 38% ($51 million) higher without the wetlands. These estimates were also noted as conservative. If wetlands are lost to urban development rather than agriculture, the increased runoff from impervious (waterproof) urban surfaces (such as buildings, roads and parking lots) is likely to further increase flood damages. You can find more details of each case study in the report When the Big Storms Hit.

Carbon storage and sequestration

As communities implement plans to reduce greenhouse emissions and reach net-zero, wetlands are again on our side. According to the Geological Survey of Canada, Canada’s wetlands hold almost 60 per cent of all the carbon stored in soils across the country. As an example at the local level, wetlands within the National Capital Region are estimated to provide climate regulation services to a value of $ 2.9 million per year.

A parting thought

Wetlands are essentially our front line allies in tackling climate change and biodiversity loss. Preserving these habitats is a cost-effective way to maintain services of financial value to our communities. It is more complex and costly to restore wetlands once they are lost, or to replace the essential services they provide with grey infrastructure.

The good news, as outlined in the recent report Getting Nature on the Balance Sheet: Recognizing the Financial Value Provided by Natural Assets in a Changing Climate, is that over 90 local governments across Canada are working to identify and value services provided by natural assets, such as wetlands, including 27 local governments in Ontario. Work within these communities has focused on valuing services that local governments are responsible for, for example provision of clean drinking water and flood protection.

So what are wetlands “worth”?

Economic valuation studies outline examples of significant, “hidden” financial benefits of wetlands, focused on specific community services.

Water filtration

In Southern Ontario, University of Waterloo researchers, Tariq Aziz and Philippe Van Cappellen found that wetlands provide an estimated $4.2 billion worth of water filtration services each year. If these services are lost, communities would need to treat the water by building and maintaining costly grey infrastructure solutions.

Flood protection

The report Combating Canada’s Rising Flood Costs: Natural infrastructure is an underutilized option demonstrated the significant value of flood protection provided by wetlands drawing on examples from across Canada. For a rural case study in Ontario (in the Credit River watershed), flood damages were 29% ($3.5 million) higher when headwater wetlands were assumed lost to agriculture. In an urban case study (Uptown Waterloo in the Laurel Creek watershed) estimated flood damages were 38% ($51 million) higher without the wetlands. These estimates were also noted as conservative. If wetlands are lost to urban development rather than agriculture, the increased runoff from impervious (waterproof) urban surfaces (such as buildings, roads and parking lots) is likely to further increase flood damages. You can find more details of each case study in the report When the Big Storms Hit.

Carbon storage and sequestration

As communities implement plans to reduce greenhouse emissions and reach net-zero, wetlands are again on our side. According to the Geological Survey of Canada, Canada’s wetlands hold almost 60 per cent of all the carbon stored in soils across the country. As an example at the local level, wetlands within the National Capital Region are estimated to provide climate regulation services to a value of $ 2.9 million per year.

A parting thought

Wetlands are essentially our front line allies in tackling climate change and biodiversity loss. Preserving these habitats is a cost-effective way to maintain services of financial value to our communities. It is more complex and costly to restore wetlands once they are lost, or to replace the essential services they provide with grey infrastructure.